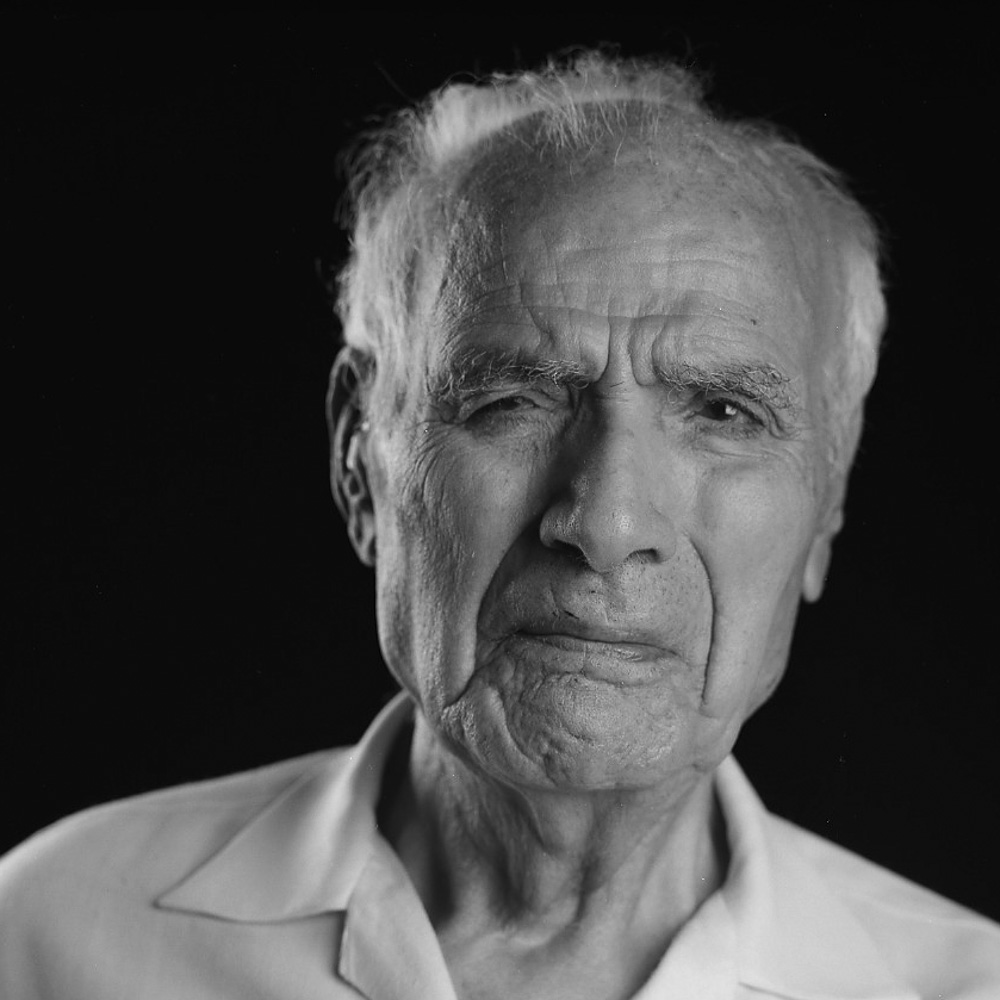

Hampartzoum Chitjian

A man who never forgot what transpired.

A humble man who never forgot the pain of losing his identity: his family, his homeland, the interaction with his community. He internalized his pain, not projecting it on others. Soft-spoken but at the same time very resolute in his feelings of sorrow and injustice, repeatedly asking for resolution for crime of genocide, both in words and deeds. His soul will not be at rest until justice has been done.

Hampartzoum Chitjian was born in 1901 in Ismael and at the age of two the family moved to Perri, a small village in the Ottoman Empire, adjacent to the Dersim. It was a modest family. The family trade was that of a chitji, a block printer, hence the last name Chitjian. It was an extended family of thirteen. By 1915, two of Hampartzoum’s brothers were living in Chicago.

By early spring of 1915, he and his father had gone to the vineyard to cultivate the vines for the following year, when abruptly a villager ran by to warn his father not to return to his house. Shortly after, Hampartzoum and his three brothers were surrendered to the Turkish authorities. Within a month, he was taken as a slave by a blind villager. A year later he escaped and that began a series of experiences, living alternately as an Armenian in the household of Dr. Mikhail and as an incognito Turk in various Turkish households. His father, mother, youngest brother, and three sisters all perished during the genocide. These six years Hampartzoum described his experiences as “living a dog’s life,” hoping someone to let him in for shelter and food. Unfortunately, as he grew older and his disguise was no longer sufficient, he realized he had to escape out of Turkey. He had no other choice.

This led him on a whole different odyssey. Three months while still within the borders of Turkey, eating grasses and raw fish, traveling at night on foot, to the point of total exhaustion. He was lucky enough to walk over the border to Iran, realizing he was a free man. At the site of a spring, Hampartzoum took a handful of mud and rubbed it across his forehead exclaiming, “This is not Turkish sun, this is not Turkish soil, and this is not Turkish air!” He prayed to thank God for the sun, the light, and the hope.

Hampartzoum’s odyssey continued as he tried to connect with his brothers in America, now in Los Angeles. From Kelisi Kand to Magoo, to Khoy, to Tabriz in Iran, where he was able to contact them through letters, he alerted them that he was still alive and of his whereabouts. Then to Khazbeen, Hamadan, Kermanshaw, Karatoot, Baghdad, Mosul, Der-Zor, Halab, Beirut, Marseilles. And then from Marseilles to Vera Cruz and Mexico City, Tijuana, and Los Angeles. After two years, Hampartzoum returned to Mexico City, establishing himself with a palateria, marrying and starting a family with a boy and a girl. In 1935 Hampartzoum emigrated to Los Angeles with his family and reuniting with his four surviving brothers.

Although for the rest of his life he was in a safe haven, Hampartzoum was haunted with the brutal and painful tragedy of his family, their way of life, and the Armenian people who had been subjugated on those lands for more than 600 years. Scattered all over the world on every continent, Armenians scrambled for refuge, thus creating a diaspora. Armenians are now integrating and establishing a new life, contributing to each society where they live. Hampartzoum’s hope was that the new generation would not be burdened with his deep, personal sorrows but for them to hear and understand the totality of this type of brutality, destruction, and loss of family.